The History of Walking Simulators: Part 1

- Walking simulators like Dear Esther are not fun to play.

- The story is worth experiencing because it can only be a video game, not a book or movie.

- The walking is transformative, meaningful play.

Introduction

2012's Game of the Year Journey re-released onto Steam this month and I have seen a subset of user reviews which seem to have a problem with the lack of gameplay. Take this one:

To dislike this game is to go against the overwhelming majority, but here I am. Journey is a work of art, make no mistake - from the world, to the music, and even in how the pause menu functions, the critics were right...but the 'game' aspect of it doesn't cut it for me. The sand sliding part leading up to one of the prettiest screenshots in gaming, and a certain stealth section, were my favorite moments - but it's a two hour game my dudes; the rest of it is just repeatedly walking to collect items that let you glide to proceed. I was expecting something more like INSIDE - one of my favorite video games(similarly praised for its art style and wordless story telling). In the end, the experience didn't imprint a particularly memorable impression on me.

This review is paradoxical to me. Journey is a "work of art", something that holds value among players that desire creativity, but it cannot be recommended due to the experience being only two hours long. The gameplay repetition makes the game shallow and therefore not worth the price? As someone who was emotionally affected by the game, it is confusing to praise it for everything I loved and end with a big red thumbs down.

To some extent, I get it. The 8-year-old game is $14.99 USD and the port has quality issues, so it's expensive AND an inferior way to experience the game. For about $15 in 2020, I could buy The Witcher 3: GotY Edition on sale, an epic fantasy game that presents hundreds of hours worth of content and advanced graphics. Hell, for 15 dollars I could purchase Celeste, a phenomenal work of art with a heartfelt story and challenging, compelling, platforming action. Journey, and the rest of the "walking simulator" genre of games on Steam, are poor value propositions when compared to games that focus on fun and the player experience rather than purely telling a story.

But walking simulators like Journey, Dear Esther, Gone Home, and The Stanley Parable started a tradition. These games walked so Firewatch, The Beginner's Guide, and What Remains of Edith Finch could run. They are all worth playing precisely because they lack typical gameplay. While some gamers may contend that a game without gameplay has no value, the first-person narratives mentioned above are critically acclaimed stories that carry the medium forward as an art form. Games without traditional gameplay work within a confined system that allows players to explore stories non-linearly, with agency, and outside of time. The pinnacle of this genre, Return of the Obra Dinn, is the first game to fully unite the gameplay with the narrative.

In Part 1, I will be defining how the walking simulator genre came to represent the best game stories available by detailing transformative gameplay found within Dear Esther, Gone Home, and The Stanley Parable. In Part 2 I will talk about what I consider to be those games predecessors (Everybody's Gone to the Rapture, Tacoma, and The Beginner's Guide) as well as Firewatch, and What Remains of Edith Finch. Part 3 will dive deep into Return of the Obra Dinn and why I believe it's the best game story ever told.

Let's Get Walking

So first we have to talk about what is a game and what is gameplay.

Reductively, all video games are computer programs that users interact with. Playing a game on Steam will typically involve controlling something on a screen and completing objectives. But the definition is broad enough to include things like interactive wallpapers and that Bandersnatch movie on Netflix and a bunch of weird stuff so to get specific we should get academic.

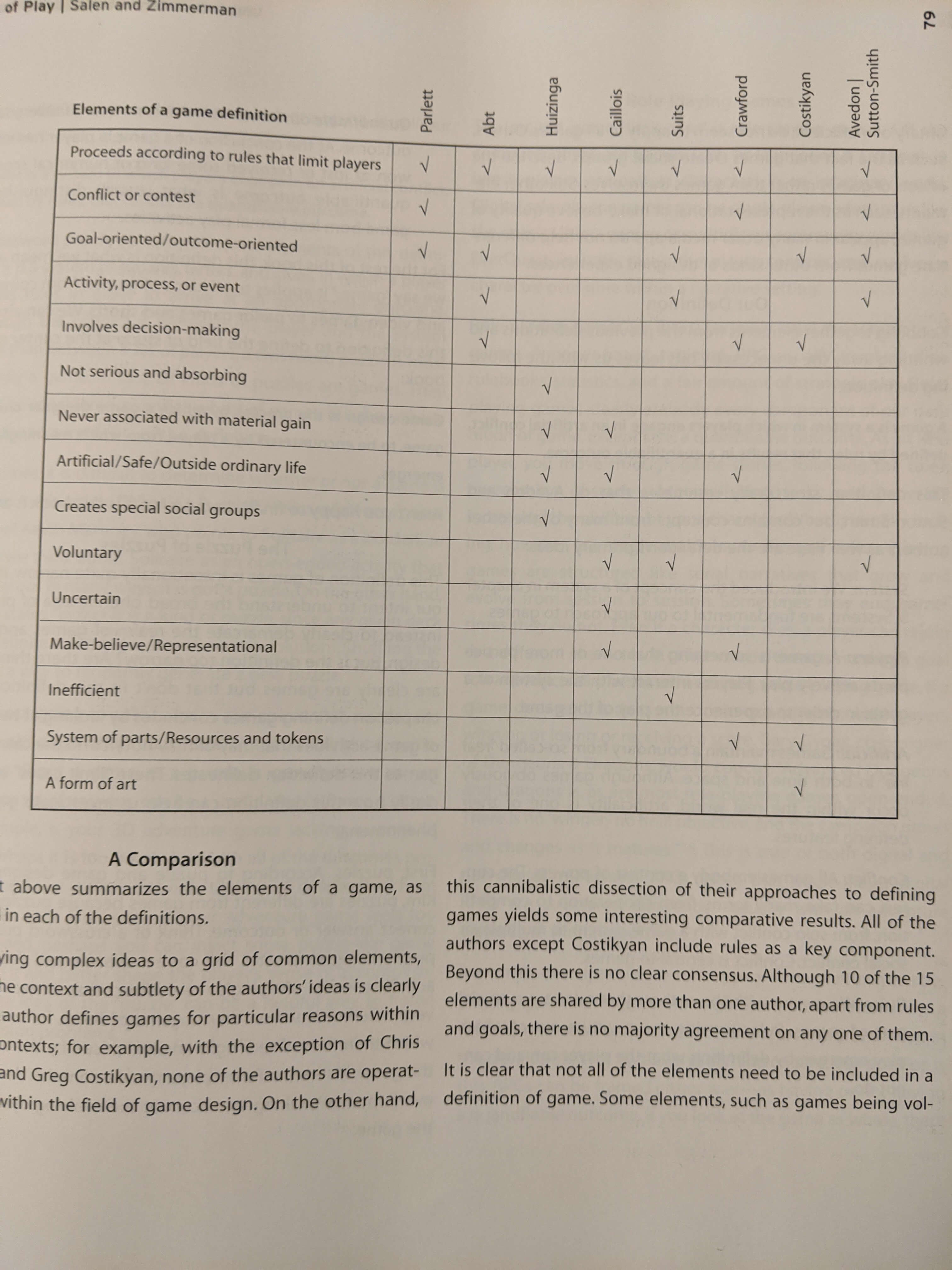

In Rules of Play Chapter 3, there are eight definitions of the term "game" presented by scholars across the discipline of game studies. Here's the table of how their definitions intersect:

Out of context, these are a bit obtuse and relate little to player interpretation. The book synthesizes these into:

"A game is a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome."

As a game designer, this lays out digestible vocabulary for defining structures in a bunch of games. And as a player, I can recognize almost every video game fits. Animal Crossing: New Horizons sets up a deserted island simulation to engage with, ready to be exploited for natural resources. I can interact with the citizens and complete tasks to earn rewards like new building features, beautiful furniture, and island aesthetic options. Pong is a system of simulated tennis where two lines battle over which side of the court the ball will land. Dodgeball is a pretend war where teams hurl rubber balls at each other violently in order to destroy the opposing force. Fun!

But the first "walking simulator" in 2012, Dear Esther, is where the definition falls apart. Systems in the game offer little to no engagement. The debut title from The Chinese Room (not the philosophy one) is their first project, started as a 2008 Source engine mod. It contains no conflict. There is no quantifiable outcome, which Rules of Play defines as:

"At the end of the game, a player has either won or lost or received some kind of numerical score."

No win or lose state in Dear Esther exists. The only action the player can take is walking to the end of the game. The setting is an island off the coast of Scotland. The player walks a path while a British man speaks, sometimes in the form of letters addressed to Esther. The interactivity is limited to WASD for movement and mouse control for camera direction. The player does not have a body. That's pretty much it, gameplay-wise.

The Walking Simulator

The term is typically used as a pejorative, but to me, it's an accurate description of Dear Esther. Game genres are often categorized by their gameplay (First Person Shooter, Real-Time Strategy, Puzzle-Platformer, Beat ‘em up). It says nothing about the narrative or plot contained within the game. The only control the player has in Dear Esther is when the next audio clip starts. A goal is never explicitly stated. There is a clear walkway through the island so instructions are not required for the experience. On the first impression, the game is a simulation of walking through a Scottish isle and listening to a lecture on English literature.

Innuendo Studio's video on the story defines the game story's success in the clearest terms.

“The only way to experience a movie is to have each frame be followed by the next frame. The way to experience a book is to keep turning pages. You consume the narrative by being pulled through it...you can’t spend more time in the book because the only way to be in it’s world is to be progressing toward the end of the book. Dear Esther only takes about an hour and a half to play beginning to end, but you have the freedom to spend 3, 5, 10 hours pouring over the details, of which there are a lot."

"...What the game can do that books, movies, and dreams can’t is allow you to linger."

Ian Danskin’s analysis shows the power of Dear Esther is experiencing a story outside of time. The game world is created with as much imagination as any movie or book. The pastures, bioluminescent caves, and dream sequences tell a story dense with symbolism. What the game fails to do well is tie the explicit narrative into the story told by the environment.

Ludonarrative Resonance

Dear Esther is the first walking simulator because the narrative found within can be understood well as a video game. But the game is impenetrable to the average gamer. The first 30 seconds require an American collegiate (or maybe British high school) reading level (Vocabulary required: longitude, latitude, correlate, singularity, alpha point, hypothesis. Symbolism involving seabirds and shepherds. The Hebridean Islands???). The prose never becomes easier to digest. There is too much quiet between audio cues and the overused metaphors confound the plot to the point of nonsense. With the help of Danskin, I would say the story is about a man whose wife was killed by a drunk driver. He escapes to an abandoned island where he muses on his experiences coping with loss and isolation. He gets sick and in the end, he climbs up a tower, jumps off, and flies.

Dear Esther’s story requires interpretation. Toward the end of the game, the island reveals itself to be less of a true-to-life location and more of a dream sequence full of otherworldly symbolism and unintelligible atomic diagrams. Unfortunately, the end result feels like listening to an audiobook synced up to a boring movie.

Gameplay, or the lack thereof, should somehow be in service of the story. Rules of Play is somewhat nebulous in defining the English word and provides 13 examples of its varied use. Instead, it lays out gameplay as:

"Playing a game such as Chutes and Ladders occurs only when players set the rigid rules of the game into motion. But the game play itself is a kind of dance that occurs somewhere between the dice, pieces, board, and the rules themselves, in and among the more rigid formal structures of the game.

Game play only occurs within games. It is the experience of a game set into motion through the participation of player.s The other two categories of play..contain a vast and diverse array of play forms. Yet even though game play is the smallest category of the three, the play of games stakes on a multitude of forms as well: the strategic competitive play of Settlers of Cataon; the performative social play of Characdes; the physical sporting play of Cricket; the lush narrative play of Final Fantasy X--all are examples of gameplay."

There is no dancing in Dear Esther. The “game play” does not engage the player. There are rules that are followed which are set in the code but there is no system like a board game. There is nothing remotely “playful” about the game, let alone it’s impenetrable language.

What it actually does as gameplay is something Rules of Play calls transformative play, which “...occurs when the free movement of play alters the more rigid structure in which it takes shape.” Unexpected forms of interaction within games can result in engaging play that transcends presupposed structures. The book uses Quake machinima as an example of a game becoming a platform for new and unique stories to be told. Transformative play can be found when interpreting the gameplay as a storytelling tool. This is how video game narrative experiences tell stories in an unparalleled way and it would be over a year until Fullbright got it right.

Perfecting the Form

Environmental storytelling is the most unique quality video game narratives have, but the narration in Dear Esther feels disjointed from the pixels on the screen. However, it would be a lie to say that it fails at environmental storytelling. Ghosts appear around the scenery in the distance, set pieces like the underwater car crash generally succeed in their symbolism, and the end is somewhat satisfying. There's a lot to be learned from it, according to this Gamasutra article. Game narratives, called “narrative play” in Rules of Play, are separated into two categories:

Embedded narrative elements tend to resemble the kinds of narrative experience that linear media provide. In Jak and Daxter, the embedded elements are the “pre-scripted” moments and structures that are relatively fixed in the game system. Any player, for example, that begins the game for the first time will see the same introductory cinematic...like text on the page of a [Select-Your-Own-Journey] book.

Emergent narrative is possible because of the way games function as complex systems. As the name implies, emergent narrative is linked directly to our earlier explorations of emergent complexity and meaningful interaction. For example, emergent narrative arises from interactions that are both coupled and context dependent….Because actions in a game are linked to one another, one change in the system can create another change, giving rise to narrative patterns over the entire course of the game.

The Game That Weird People Got Mad At

Gone Home from 2013 is one of the best games that combine embedded and emergent narrative. Set in rural Oregon in 1995, the player takes the role of Kaitlin Greenbriar, a college student returning from studying abroad. It starts with an answering machine message, a title drop, and luggage on a porch. A note on the front door of the house says it's locked. She must find the key to start the game.

This game tells a story better in this 30-second sequence than two hours with Dear Esther. Not only does the player know who they are and what their objective is, there's a clear conflict that requires player action to resolve. The player must interact with the environment to learn the story instead of being only an observer like in Dear Esther. Through finding the house key under the Christmas duck the player learns a plethora of information:

- Nobody is home, even Sam, Katie's sister. She left a suspicious note.

- This family house porch is used and "lived-in". There's an empty mug sitting next to a comfy chair and table setup.

- The porch is quite large, implying the house has many more interactions within.

- The Christmas Duck is familiar to the character but not the player. She knew the spare key would be there, indicated by the change in the item label (Good ol' Christmas Duck).

- The house is unfamiliar to both the character and the player. It's confirmed later in the game that the family moved while Katie was in Europe.

Environmental storytelling is what makes Gone Home the next step in walking simulators. It's engaging because it is a game you actually play. It has explicit objectives and conflict: clues and UI elements inform the player what to do next while the goal is to find Sam and figure out why the house is creepily empty.

The game world feels like a real, lived-in house relatable to anyone familiar with American suburbia. Narratively, Katie is compelled to learn about the house, why it's empty, and why she can’t look for Sam. This is achieved by completing smaller objectives that enable transformative play.

Going to the Home

Errant Signal’s Gone Home video calls the game “an archaeology dig”.

"...a site where we find artifacts to tell us a story of who these people are and what happened to them. Clues litter the walls, they’re scattered in desk drawers and they line the floor. Sometimes there are letters and notes for you to read, sometimes there’s a sentimental object you can hold and examine, and sometimes there’s an environmental detail that makes the house seem lived in and real.

...While it might not look that way at first glance, there is a full-on story here. Complete with revelations and side-characters and episodes. While the game’s hook might be the mystery of where everyone went, as events are uncovered, characters will become fleshed out and they’ll have gone through entire arcs. And that’s the meat of the game. It’s not a puzzle you solve, but a story you slowly reveal."

"The impulse you get in Fallout or Skyrim to search every nook and cranny of a room for objects is just as powerful here, and I think it's a testament to the way the game sucks you into its setting. That searching a teenage girls room for 1990s music magazines is as captivating as searching a Fallout shelter for bullets. There’s a subtle form of game design here, and it’s not in the way that balancing a lot of intricate systems is subtle. It’s subtle in the sense that it’s conscious when to apply traditional game systems at all. Providing just enough tactile feedback and mechanical engagement to keep you playing, but only that amount, in order to keep the systems themselves from drawing the focus away from the Greenbriar’s story."

This feeling is the core gameplay loop of every walking simulator. What makes Gone Home an actual game is the embedded narrative told through narration and text, blended with the emergent discoveries through gameplay interactions. Environmental storytelling in Dear Esther like the broken down car or the paper boats makes no sense without context. It relies on a series of disjointed voiceovers. The house in Gone Home has one of the best settings for a walking simulator because of how much information can be gleaned from something as simple as a bill from the movers or the cover of Katie's Dad's book, The Accidental Savior.

Let's Get Meta

So what happens when the emergent narrative and embedded narrative do not work together, but instead actively fight against each other?

2013's The Stanley Parable takes place in another hyper-informative space: an ethereal office building. Originally a mod for Half Life 2 from 2011, the player controls Stanley, an office worker whose computer terminal is malfunctioning. He stands up from his desk and walks through one of two doors. Kevan Brighting narrates beautifully, which is revealed to be the game’s central conflict. Similarly to Gone Home and Dear Esther, The Stanley Parable leans into the trope of the unreliable narrator in a way that only a video game can do. As Stanley chooses to obey or not obey the narration, the story forks. An evil conspiracy is unveiled that only Stanley has the power to (attempt to) stop. Or he becomes a playtester for a game preventing the death of an infant. Or he falls out of a window and dies.

Narration in walking simulators thus far are not omniscient. Dear Esther's player character is nebulous, and Gone Home's voiceovers are distinctly Katie. The narrator in The Stanley Parable has direct influence over the actions of the main characters. Responding to the rules placed on the story by the narrator is how the game is played.

The End Is Never The End Is Never The End Is Never The End Is Never The End

The gameplay of The Stanley Parable relies entirely on surprising the player with the narrative. It succeeds in its comedy by subverting the expectations typically placed on a first-person video game. Folding Ideas video The Stanley Parable, Dark Souls, and Intended Play, Dan Olson uses these games narrative similarities to demonstrate their success:

"These two games are all in all, very different from one another. But they’re illustrative for our point here because they both utilize elements of intentional disobedience.

Games have a dimension of interaction that means there's not merely intended interpretation, but also intended play….interaction in games means games can do something that other media rarely can outside of very experimental context. Which is, to tell the participant to do one thing while expecting them to do another.

Any open world game has a moment where the player is told to do one thing, and can then choose to immediately turn around and go the other direction,opting instead to spend dozens or even hundreds of hours doing anything else but the thing they were asked to do.

Games are constantly telling us to do one thing and then waiting to see if we actually do it. The Stanley Parable uses this to create a conflict between the player and the game, but at the end of the day that’s just a costume put on an otherwise ordinary interaction. The narrator is simply a disembodied antagonist like SHODAN or GlaDOS, and much like GlaDOS the narrator of The Stanley Parable tells you to do or not do specific things while the game fully expects you to ignore those requests.”

The narrator is the embedded narrative and every anticipated player choice is the emergent narrative. The Stanley Parable uses the narrative discovery process to great success. The humor relies on the player making choices that are nonsensical in the game world context and rationalizing them into a spectacle, like floating through space. The Stanley Parable is hilarious and personally, one of my favorite games.

Finishing our First Walkthrough

So, walking simulators work as games for a specific reason. Experiencing a narrative by walking through it leads to storytelling that can work like a dream. The world's found in these games are similar to real-life enough so that it contextualizes the fiction found within them. Player actions build a narrative in a video game when done right and after The Stanley Parable's release, walking simulators that followed expanded the ideas of what video games can achieve with world-building.

Next time we'll talk about how The Chinese Room, Fullbright, and Crows Crows Crows followed up their successful games and the three games that followed which I see as important to the genre.