The History of Walking Simulators: Part 2

- All the games I spoke about in Part 1 were critically acclaimed

- The games those companies made after had acclaim as well

- They did not sell

- But were they unsuccessful?

Welcome Back!

In Part 1, I talked about what a game is when someone calls it a walking simulator. Gameplay for a "walksim" is not controlling the player character movement. Instead, Discovering the story is how the game is played. Dear Esther is primarily a game because of its artistic storytelling in an interactive medium. That game, along with Gone Home and The Stanley Parable, is what I considered to be the beginning of the genre tradition.

In Part 2 I am going to talk about what makes a walksim a "good" video game using aesthetics. These games are essentially virtual interactive theater. We will look at The Chinese Room, Fulbright, and Davey Wreden’s projects released after their successful games. The plot, story, narrative structure, and gameplay innovate and expand what it means to explore a narrative in the first person. But unfortunately, they did not sell well.

SPOILERS: The games covered are Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, Tacoma, The Beginner’s Guide, Dear Esther, Gone Home, and The Stanley Parable. I also spoil The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, Soma, and Yume Nikki.

RIP Walking Simulation

To start, I want to talk a bit about things I missed in Part 1.

I was linked to a highly relevant article by Doc Burford titled Death of Walking Sims. He details the success and failures of these games in development terms, noting that The Chinese Room shuttered its doors and Tacoma initially sold barely 1% of the copies of Gone Home.

Burford is a gamedev with industry experience. Paratopic, his 2018 "walksim", can be interpreted as a response to the genre. His viewpoint concentrates on how the gameplay disconnects gamers who enjoy “hardcore” experiences like Halo on heroic mode from enjoyment.

When it comes to walking sims, the hardcore players are technically correct, but actually wrong. A “game,” is, more or less, a form of structured play, and while that’s a remarkably broad definition, it doesn’t necessarily cover walking sims. In the same way that “real time strategy” isn’t the best name for the RTS genre, “video games” isn’t really the best name for the medium. Sure, it worked when the only games that existed were titles like Pong and Pitfall, but even then, 1979’s FS1 Flight Simulator could never be classed as a game. There are plenty of things that most people would consider to be a “video game” even if they’re not truly games, and walking sims are no exception.

But even if walking sims weren’t considered video games, would it really matter? Sure, they have more in common with art installations than competitive sports, but so what? Whether a walking sim is a ‘real game’ or not doesn’t stop it from existing and can’t stop it from being praised or discussed. Taxonomy only goes so far; the work cannot be dismissed simply because someone might have got the classification wrong.

“Video games” are a misleading term for walking simulators. This helps understand the author's intent when talking about a walksim. What makes a good video game story is the “playing” of the story.

Getting the player to enjoy that can be somewhat difficult. Burford emphasizes the importance of making the experience enjoyable.

At its core, I think the genre’s simplicity is the problem. It’s a fundamentally reductive genre; all you do is walk, usually listening to someone else’s story take place. While that is a mechanic in and of itself, it rarely becomes anything more. A walking sim’s story should be about you exploring the environment, because you are the point-of-view character, but in walking sims, the POV character is usually the person doing the voiceover instead, telling you another story entirely. You’re just there to press W and trigger the occasional audio clip. At best, you’ll have to consider the environment, contrasting what you’re hearing with what you’re seeing, like an art installation. Compare that with a shooter, which is much more engaging, not just because there’s more to do mechanically, but because shooters work to keep things varied.

Fundamentally, there’s nothing really wrong with walking sims. It’s just that other games handle the same topics in ways that invite more participation, and most players are more interested in being the characters they play than hearing about those characters from an epistolary audiobook. They’re not that popular because they’re fairly limited as a form, and once the initial newness wore off, there wasn’t that much to support them.

I’ll be talking more about this perspective in Part 3.

And All The Players Merely Players

Burford is right. Games like Dear Esther and Gone Home are not fundamentally engaging. However, I would argue that a walksim can only be successful because of player engagement and immersion.

Let’s use some aesthetic philosophy to lay out what I’m talking about. Jacques Ranciere’s The Emancipated Spectator notes two major problems with the passive viewing of art:

“...First, viewing is the opposite of knowing: the spectator is held before an appearance in a state of ignorance about the process of production of this appearance and about the reality it conceals. Second, [viewing] is the opposite of acting: the spectator remains immobile in her seat, passive. To be a spectator is to be separated from both the capacity to know and the power to act.”

Ranciere never mentions interactive stories like video games. The relationship between the player and the video game is unique (his preferred example is the audience and theater). Theater provokes thought in a passive viewer because the actors are real human beings. There is no concern for “immersion” when the experience is happening in real-time and space, mere yards away from the audience's eyes. Video games involve the audience/player in the story and give them virtual control over it. In a walksim, that means progressing, interpreting, or even ignoring the narrative. The power of video game stories is immersing and, in essence, making the player an actor in the story. Sometimes that character is defined, and most of the time the discovery of who that is informs the narrative.

Yume Nikki: Genre Tricky

The story of Dear Esther is considered, by me, to be the first walking simulator because of perspective. 2004’s Yume Nikki came first, and he gameplay is primarily walking. But in that game, there is a level of passiveness to the player control. It's presented as a 2D RPG and this is both a visual and a cultural barrier. I can see a character walking on the screen that is clearly not myself, and the game structure reminds me of traditional Japanese games like Dragon Quest. I have an expectation that it will be similar to others in that style, and the betrayal of that expectation informs the story. In Dear Esther, the first-person camera and lack of UI hide gamification typical to a shooter or platformer. This requires the player to question their surroundings as they would in the real world.

I will be talking about Yume Nikki more next time, but like Dear Esther, the game is also culturally obscure. Besides every NPC and the name of the game itself being in Japanese, the player character Madotsuki is a hikikkomori. This appeals to players familiar with Japan and other terms such as seppuku. The popularity of Japanese culture has exploded over the past decade, which has widened the game’s audience. Yume Nikki was localized to English in 2012 by Playsim, and they remade the game in a 3D engine two years ago.

It's All Relative

Yume Nikki illustrates one of gaming’s biggest storytelling barriers: cultural relativism. In a walking simulator, the player needs to feel as if the experience is real. British/European players have an easier time understanding The Chinese Room’s games because the accents, vocabulary, and geographical references are familiar. My American heritage held me back from being immersed in Dear Esther. But, my Japanese heritage helps me feel better connected to Yume Nikki.

Like many other games, walksims are fun because of story discovery. A player can only be engaged as much as they understand the universe the game takes place in. To go back to Ranciere for a second:

“To dismiss the fantasies of the word made flesh and the spectator rendered active, to know that words are merely words and spectacles merely spectacles, can help us arrive at a better understanding of how words and images, stories and performances, can change something of the world we live in.”

The spectacle and "flesh" here are virtual worlds, something that tech has only been able to realistically emulate since the early 2000s. Versimilitudinous environmental storytelling, combined with narration and audio, is the way walking simulators tell stories.

Yume Nikki is a phenomenal piece of interactive fiction, but it’s outside of the genre because of its presentation. This is how I see this game and others as different from what I set out to initially cover.

Let’s Get Raptured

After Dear Esther’s successful release, The Chinese Room made one more original interactive narrative before ending independent operations. Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture is the story about Kate Collins and Stephen Appleton, two scientists who return to Stephen’s childhood pastoral English village to study the night sky. The player begins the game in the empty township of Yarbrough. Everybody is gone, presumably, to “the Rapture”. There is a cast of about eight characters who, through replayed holograms, inform the player of the events that lead to everyone in this town dying.

The game experience from their debut title is improved upon twentyfold. Environments are no longer barren rock formations and scattered obtuse symbolism. Instead, a vast collection of lived-in spaces including tons of houses, businesses, and community centers littered with artifacts to view (but not interact with). The graphics are PS4-level beautiful; the landscapes are impressive, and the game shines in its special effects. Interactivity is expanded to starting audiotape recordings from Kate and opening doors. And most importantly, the addition of another character; the light.

The addition of an NPC that leads the player creates a connection to the story that their other game lacked. This review from Games as Literature highlights how successful this is:

“...there needs to be some kind of structure, of course, which is accomplished by the light that guides you around the town and it’s both one of the best and worst things about EGTTR. At it’s best, the game feels like one of the most smoothly flowing exploration games I’ve ever played. I’d follow the light to the next event it wanted to show me, then I’d notice something that’d look interesting off to the side so I’d deviate from the path, find something Light had explicitly tried to lead me to and when I explored it all and due time, see the light flickering in the distance and go to join it again. It’s a great form of player guidance in that it actually feels alive. Like it’s some kind of force that actively wants to show you something but isn’t completely beholden to your will and actions. It flits in and out of your presence, always leading you somewhere else but never depending on your cooperation. This is improved even further by the way its behavior changes in each chapter. It can be fairly subtle, but the light seems to take on characteristics of the subject of a given chapter and how it moves, and in one important case, how it looks too. "

The care and thought put into the characterization and dialogue in EGTTR are crafted for player empathy. As the game is played, the world evolves with the narrative; the weather shifts from the milky way night sky to rattling rain to lightning and thunder.

The comparison to the theater is easy, as the story is told primarily through character dialogue. EGTTR’s story is human, universally relatable, and still quite British. The plot is deeply layered with things like Steven and Lizzie’s former engagement, Kate’s ex-pat alienation, Wendy’s estranged relationship with her brother, and Father Jeremy’s crises of faith.

Everybody's Gone

By the end of it, the player has seen each character’s final living moments. There is no Rapture; Steven and Kate brought an interstellar being to Yarbrough that creates a pandemic, resulting in the military calling in an airstrike and gassing everyone to death. Steven confronts the monster, who is revealed to be the ball of light, and immolates himself. Kate’s fate is left to interpretation (I think she becomes “entangled” with the ball of light).

As an interactive story, EGTTR surpasses Dear Esther in every way; the player engagement is improved, the story is easily understood, and the setting is beautiful. It’s also littered with straightforward environmental storytelling that immerses the player in a way Dear Esther sorely lacked. I was touched by the plight of Kate; stranded in a foreign village where everybody judges her, while her partner is still in love with his ex. The spiritual nature of her scientific research kept me engaged and sympathetic.

Unfortunately, EGTTR did not succeed as a video game product. I personally think The Chinese Room contributed immensely to the video game medium. It makes sense when the studio name is explained; The Chinese room argument is about the unknowable barrier between virtual and biological experiences. This metaphor fits into their storytelling style quite well; in both of their games, there is a juxtaposition between the player’s immersion and lack of interactivity. Even though it informs the story, this makes their games not very fun.

Tacooooomaaaaa

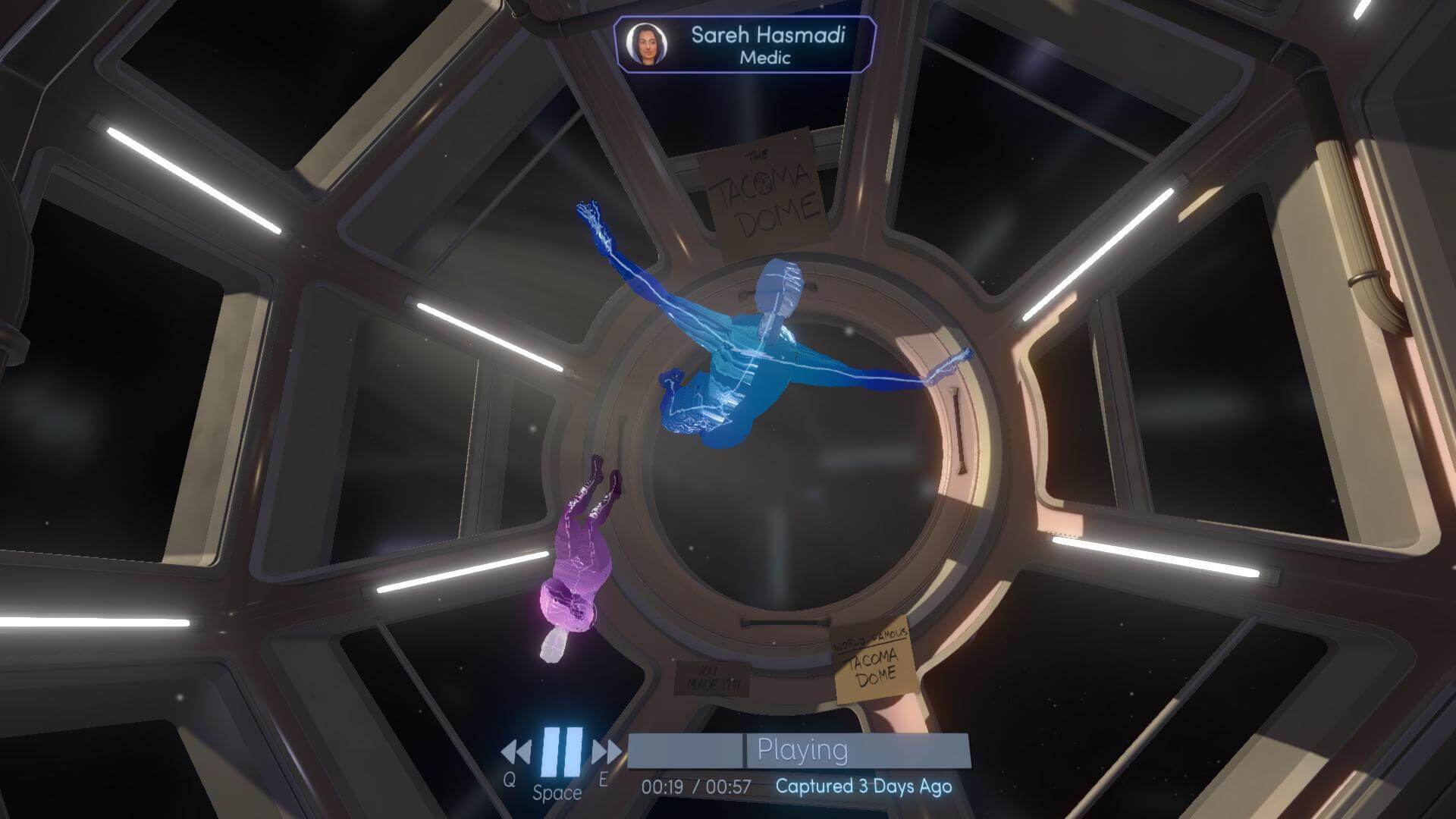

Gone Home’s successor, 2017's Tacoma, has a lot going for it in terms of accessibility. While Fullbright’s first game creates a lived-in house that informs the player with each interaction, Tacoma turns that into a huge space station inhabited by six characters and a benevolent corporate AI named Odin.

Player character Amy Ferrier must investigate what happened onboard the corporate spaceship Tacoma, owned by the Venturis Corporation. Like EGTTR, the story is primarily told through replayed dialogue as holographic projections. Like many of the sci-fi elements, Odin helps the player's investigation into what caused the crew to disappear. The sci-fi setting is easy to get into if the player is familiar with something like Mass Effect or Star Wars.

Gameplay in Tacoma is walking through these replays, which sometimes involve multiple conversations happening at once. Tacoma innovates by allowing the player to repeat an experience, but learn something entirely new. Noah Caldwell-Gervais SOMA vs Tacoma video explains it well:

“The primary mechanic the player does have in Tacoma is a way to view and rewind conversations from entire segments of the station, meaning you end up walking in-between different rooms nad following disparate, individual threads of the same interwoven conversations from different perspectives.

…[the mechanic] allows you to trace the threads of conversation back in time and back through the space you’re inhabiting in the present tense. Like SOMA, it tells the story in a way that only games are capable of; this layering, wandering past the rooms as the protagonist while the wireframe memories reenact the past going at your own pace, rewinding, pausing, diverting your attention to follow a character as they break off from the conversation to pursue some other goal, neither film nor theater nor print can do that. It’s closest to theater, certainly, and a lot of the writing and delivery of Tacoma has the feeling of a small-stage production, but you could never ask live actors to pause and rewind themselves with it being either silly or artificial.

“In terms of mechanical construction as games, they’re even very similar. Tacoma cares much less about standard game features than SOMA however, and its happy to pull more from live and experimental theater than standard video game tropes.

...A lot of this noise comes around to definitions; a video game should primarily be a game, right? With gamey stuff to do? Well, SOMA is not very much a game in a stock standard configuration and not really at all when you remove the monsters; it’s interactive fiction. An explorable space where first person perspective can pair with a natural pace of navigation and discovery to tell stories in ways that other mediums, passive mediums like print or film or the sound of my voice, could not ever convey the same way. “

Performing the Game

As a science fiction story, Tacoma is straightforward in its metaphor. Like Gone Home, environmental storytelling is overflowing with information that engaged the player. The sci-fi world is realistic and reminiscent of other corporate dystopias like Alien or Blade Runner. The setup for the story is not obscured; there are a lot of expectations set up once the premise is understood. When the dialogue and environmental pieces inform the player, the discovery of the story is less mysterious. I already know corporations are not our friends and them in sci-fi view human beings as a commodity, because they are already considered "obsolete". Odin is a constant reminder that the player is being observed and recorded for profit, and any characterization involved with it will end in some kind of betrayal.

And while the story is strong, the narrative lacks subtlety. Gervais' SOMA comparison(which had a walksim mode added in a patch) is useful here again:

As you explore and listen, there is a tangible feeling of really getting to know the characters; youre given an opportunity to see them in moments they might not want to have been seen in moements of grief moments of doubt, you rifle through their drawers, and read their emails, and it’s a lot closer look than you would ever get in real life into the private lives of strangers. Which may be theonly real handicap of Tacoma; as intimate of a portrait of the characters as it is, it’s so carefully manicured to give rapid-fire insight over it’s 3 hour length that the insight can feel artificial. A dramatic conceit. Real people are rarely read so plainly, and seldom do we leave so many convenient clues into our past and present selves.

As the game progresses and the spaceship opens up, Amy learns about how Venturis intentionally sabotaged their own ship. As company property, the ship AI is bound not to say anything by its owner but wants to save the innocent lives of the gig-economy subcontractors that kept it running. As a story, it's a great allegory for what it means to be a worker in a post-work society that has robots to do everything.

Like Gone Home, environmental storytelling is overflowing with information that engaged the player. However, this sometimes works against the effectiveness of Tacoma because of the type of story they're telling.

All the Game's a Stage

It’s interesting that both The Chinese Room and Fullbright seem to have evolved the genre in similar ways. For example, they added another “living” character and dialogue was both spoken and blocked by artificial figures.

Comparing the two, I would say that Tacoma told the narrative more effectively with less engagement. Their use of a sci-fi setting allowed for a plethora of information and left little to the imagination. Story-wise, EGTTR was way more engaging. The mystery is set up right from the title of the game, and interactions inform the player in a more ambiguous, spiritual way. The religious overtones and vagueness in the science work never distract the player.

But Tacoma has way more player interactivity. The immersion gained from the experience, interacting with the sci-fi chat logs and floating through the station, is something The Chinese Room just does not do in their games.

It can almost be said that the environmental storytelling in Tacoma works too well, and if the settings of both of these games were switched, it would improve them both.

The Beginning: A Monologue

Davey Wreden and William Pugh, developers of The Stanley Parable, do not currently have a follow-up game together. But Davey Wreden, their narrative director, released The Beginner’s Guide in 2016. The game starts in an abstractly-modded Counterstrike map and is narrated by a fictional character named Davey Wreden, who also wrote The Stanley Parable. The audience is led to believe this is the real Davey with clues like an email address to reach him at. The narrator addresses and instructs the player directly, as in The Stanley Parable, but there is a distinct lack of agency. This is Davey’s story.

There is a required read before talking about this game: Davey’s blog post from 2014 titled Game of the Year, an award The Stanley Parable won from several publications.

Wreden’s struggles with popularity should be read with this in mind, which is something Errant Signal’s analysis tried to shy away from.

“Coda states that Davey has infected his personal space and that Coda can’t give Davey what he wants, but that Davey isn’t Coda's problem to solve to begin with.

Again, this is how you would talk about a Facebook stalker, and the result of all these little touches is to make the relationship feel coded as such. None of this is to suggest that coda is literally a woman, though given the unreliable nature of the narrator that's not impossible, but it does present an interesting way to further frame the game’s main relationship as poisonous. Davey is a creeper who violates privacy and trust after placing someone else on a pedestal and is obsessed with seeing them again.

...in making video game Davey the villain for attempting to read way too much personal stuff into games that actually had very little personal stuff in them, I do think The Beginner’s Guide is set itself up as something of a trap for critics. See, The Beginner’s Guide came out nearly two years after Davey Wreden, the real flesh-and-blood human being Davey Wreden, wrote a blog post about suffering anxiety and depression after the success of the Stanley parable. How he felt like he lost control over what the game meant and what he liked about it to his audience, and how he searched desperately for external validation only to find that hunger ever-growing.

And it’s really tempting to draw parallels, to argue that this game is a direct result of those emotions and those anxiety. That Coda and video game Davey are really two parts of the same person; the creative, impossible-to-know muse making things for their own sake, and the post-Stanley developer desperate for validation.

But to say something like that definitively is to make the same mistake that video game Davey did. To claim that I see the person in the work, to bring in my own lamp posts from outside the game and say there’s signifiers of meaning. Well, I’m not gonna fall for that and I’m going to keep this video wholly within the text.”

In a fictional story, especially one that’s presented as autobiographical, the author’s life context is vital to the text. Davey’s experience struggling with popularity reveals the truth to the story that Franklin does not want to acknowledge; Coda is a representation of author Davey’s desire to be the source of his own validation.

Guiding your Code

Coda is presented as a gamedev who never releases their games. They have no desire to, even. Author Davey sees something intrinsically valuable about these games that Coda cannot seem to acknowledge themself. As the player explores these game worlds, the blatant symbolism is displayed in a raw way that stories rarely exhibit. Davey breaks it all down for the player in real-time, drawing a clear narrative for all of the games Coda has made in their relationship, as well as explaining what these games meant to him.

But Davey has been shunned by Coda. Davey wound up exposing Coda’s games to others as a way to seek validation in himself. The result is Davey putting together the collection of the work and releasing it publicly as an act of desperate flagellation. He needs Coda back in his life in order for him to interpret himself. Author Davey has created this character as an external drive to be a great storyteller, gamedev, and human being. Here's Danskin's analysis, titled The Artist is Absent: Davey Wreden and The Beginner's Guide:

“It’s a project that doesn’t so much break the fourth wall as to be seemingly constructed without one.

So our narrator, Davey, flat-out tells us how the game is meant to be interpreted, which is to say - it isn’t. This is a walking tour of a number of small art games by his friend Coda, and Davey is going to tell us as we play what he thinks they mean.

...These games were made by Coda for [their] own enjoyment, not for public consumption, so to really “get” them you need both a player’s perspective and a designer’s perspective. During play, Davey makes walls transparent to reveal architecture that is built but the player would normally never see, and he lets the player into rooms they normally wouldn’t have access to.

What the player comes to understand by the end is that Davey has, in fact, been making far deeper alterations. He’s not just making the games playable or more understandable, but, from his perspective, he’s making them more coherent, and those alterations he didn’t admit to us.

When Coda discovers that Davey has been sharing altered versions of his games with other people, he makes one final game just for Davey and then quits game design entirely. And that last game is unplayable without Davey’s meddling…

....by the end of the game, the player is supposed to realize that none of it is true. That understanding is part of the text; there is still a fourth wall.”

The end scene, where character Davey pours his disgust for himself out onto the player, is beautiful. The fourth wall, the barrier between author and audience, is shattered. The Beginner’s Guide is a meditation on what it means to be a creative person. It engages the player to see something in an artist or work of art that is emotional and often uncomfortable. Coda’s games are unfinishable and not fun, and Davey cheats the player into completing a lot of them. The relationship between character Davey and the player keeps him separate from what he wants to truly express.

The Meta of it All

The plot in The Beginner’s Guide is a phenomenally told story from an unreliable narrator who steals another creative’s work. That has been done before in games like The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, but Davey’s autobiographical insert adds a layer of complexity that other mediums rarely reach. The player is interacting with author Davey by playing the games Coda’s fictionally made, hearing the narrative character Davey is telling, and interpreting both what the fictional games mean to them and what the games mean to character Davey. I cannot think of another video game that handles player interpretation in such a direct manner.

When an audience goes to watch a piece of theater, there is a sense of community. The human beings performing on stage are real and as a spectator, there is no imagination required. The same thing is happening in The Beginner’s Guide; unlike EGTTR or Tacoma, the player is not a fictional character. In fact, as Franklin Innuendo Studios both acknowledge, this story is clearly fiction (even though it's presented as nonfiction).

Conclusion and Going Forward

Like a lot of great stories, the experience of The Beginner’s Guide is greatly improved when considered in the context of their relationship with the developer. Autobiographical video games are few and far between, and in general, have little appeal when compared to a story like Master Chiefs. Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, Tacoma, and The Beginner’s Guide all exceeded my expectations and should be enjoyed by anyone who loves games and stories. But why didn’t they become as popular as their predecessors?

In the context of this specific genre, it seems that they cannot compete with what some would call a “mainstream” video game. When Dear Esther, Gone Home, and The Stanley Parable set a standard, in trying to surpass it, the devs did not effectively communicate what makes a walksim massively appealing. I hope I've done that a bit here today.

In Part 3 I’m going to try and talk about more games! Genre-adjacent games: adventure, horror, and puzzle games like Anatomy, The Witness, Gravity Bone, and Jazzpunk. These game genres are most similar to walksims and inform the player experience. In the future I will be covering The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, Firewatch, What Remains of Edith Finch, Return of the Obra Dinn, and Death Stranding.

Is there a video game you think I should talk about? Comment on this article below or ask me about it on Twitter!